Service Architecture at SoundCloud — Part 2: Value-Added Services

This article is part of a series of posts aiming to cast some light onto how service architecture has evolved at SoundCloud over the past few years, and how we’re attempting to solve some of the most difficult challenges we encountered along the way.

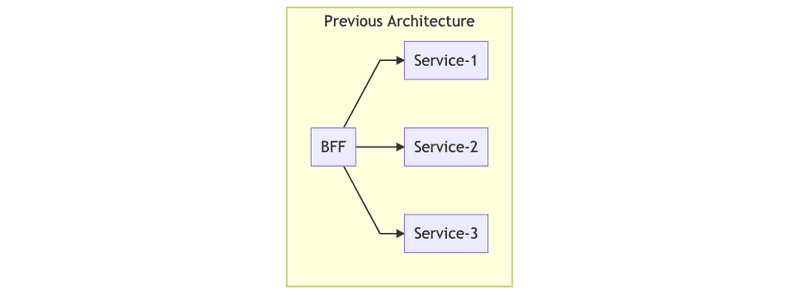

In the first installment, we covered the use of the BFF pattern within SoundCloud, detailing its pros and — more significantly — its cons. While the BFF architecture comes with many benefits, such as optimizing backends suited for different clients and a higher level of resilience than a shared single backend, its implementation at SoundCloud became problematic over time. Unnecessary complexity and duplicate code developed. Even worse, we had business and divergent authorization logic living in each of the BFFs, which is a dangerous pattern, as the maintenance and synchronicity of this code is of paramount importance. It became clear that we needed a different approach: Enter Value-Added Services (VAS).

Value-Added Services

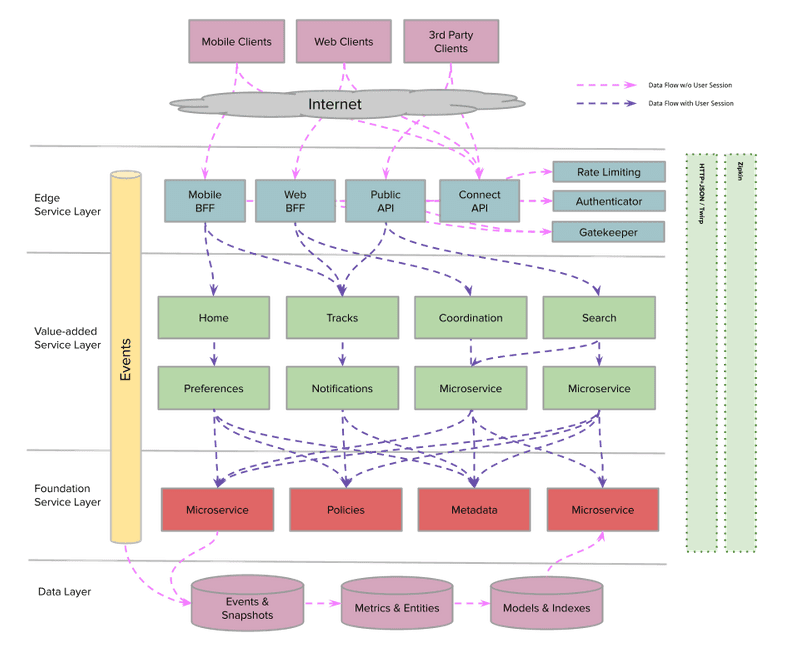

First, let’s cover the different service layers at SoundCloud that make up this architecture.

- Edge: This layer provides API gateway capabilities and is where our BFFs live. The BFFs are published and maintained dedicated APIs that are tailored to specific client needs.

- Value Added: Services in this layer consume data from other services and process them in some way to build rich experiences for users.

- Foundation: This is a low-level service that provides the building blocks around a domain.

It’s also important to understand the building blocks that come together in Value-Added Services. These are all well-known domain-driven design concepts, which you can read more about in this article.

- Domain: A user or business concern that can be used to draw boundaries/scope around service integrations.

- Entity: An entity is an object that has an independent identifier and a lifecycle.

- Value Objects: Value objects contain metadata related to a given entity; they’re also tied to the lifecycle of the given entity.

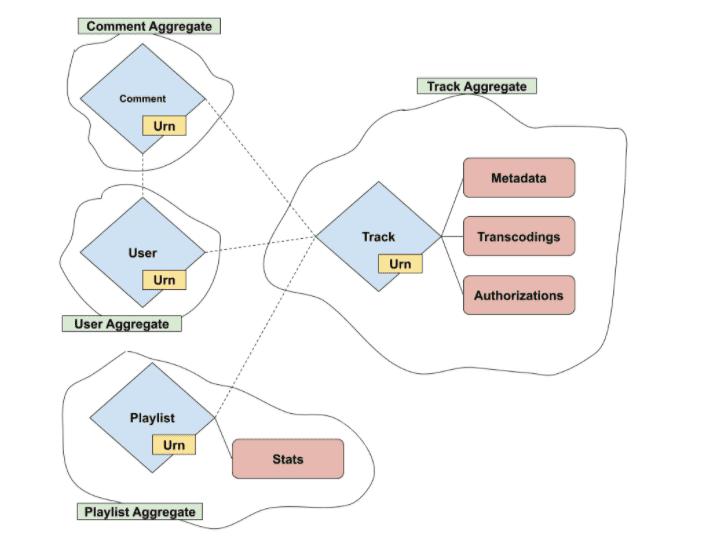

- Aggregate: An aggregate is a collection of one or more related entities. An aggregate has a root entity called the aggregate root. Aggregates can also contain references to other entities, but not the referenced entity metadata. It’s then up to the consuming services to call other services to synthesize the entity references.

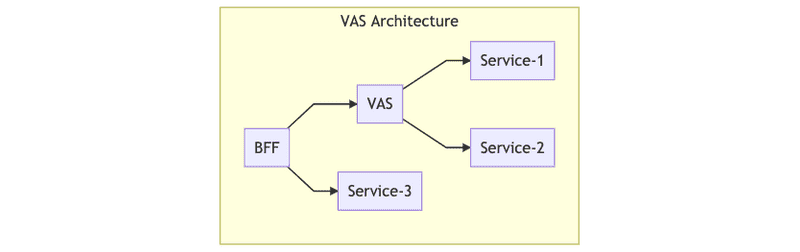

Value-Added Services are business services responsible for returning an entity and its associated value objects (in other words, an aggregate) to the caller. It’s important to note that a VAS is not responsible for synthesizing metadata for any associated entities. This allows for a nice separation of concerns — along with a centralized point where metadata and authorization rules for a given entity can be defined. A VAS can then orchestrate calls to these services to synthesize and authorize aggregates to then return to the BFF.

Let’s apply these concepts to real-life examples at SoundCloud. An example entity is a track, which has associated value objects like metadata, transcodings, and authorization policies to determine visibility. A track is also connected to an owning user, but since this is another entity, it only contains the user ID as a reference. If a consuming service has a track ID it wants to resolve, it’ll then call the Tracks VAS, which takes care of ensuring that the track is visible, and then it returns the according track aggregate.

Previously, if an end user wanted to fetch a track, the request would be sent to the BFF. It would then be up to the BFF to determine whether the session user was authorized to view this track and, if so, to synthesize the external track representation to return back to the user. This would involve calls to various Foundation services that are individually responsible for returning both authorization information and track metadata.

However, once the Tracks VAS was introduced, this pattern changed. All the duplicate logic surrounding calls to Foundation services in the BFFs was moved to the Tracks service, which now took care of synthesizing track aggregates for the BFFs, in addition to handling context-specific track visibility and authorization. The BFF was then responsible for mapping those internal track aggregates to external representations for the clients to consume.

Of course, nuances in how the BFFs behave in fetching tracks remains, but all shared code now lives in a singular codebase. Integrations requiring track aggregates are now as simple as querying endpoints exposed from the tracks VAS, removing the need to reorchestrate calls to Foundation services, and maintaining a guarantee that authorization is properly taken care of.

Evolution of VAS at SoundCloud

Now that we’ve explained the basis of VAS and how we integrated it into SoundCloud for tracks, we’d like to share how we adapted the same architectural pattern for the case of playlists. We’ll also outline the challenges we encountered during the process of evolving our architecture toward a VAS landscape.

As we already discussed, in 2019, we started the development of a Tracks service using the concept of a VAS. That was the first implementation of such a concept in the organization, and it helped us validate a model to apply to the rest of our entities. In 2020, we began a major refactoring of our Public API. The codebase of the Public API was divided between the Public API component of the Mothership monolith and the Public API BFF, which is a facade of the Public API. The refactor involved migrating all endpoints from Mothership and rewriting them in the Public API BFF.

Rewriting all track-related endpoints (all the endpoints that were returning the representation of tracks) was an easy task, as we already had a Tracks VAS up and running, so we just needed to connect the Public API with the Tracks service.

However, we also needed to rewrite all the playlist-related endpoints, but we didn’t have such a VAS. So we had to decide whether to duplicate existing authorization and fetching logic from other BFFs and move it to the Public API, or to create a new Playlists VAS to be the central service to handle fetching playlists logic and to make the Public API BFF dependent on it. The latter solution was, for us, the most attractive, as it would require refactoring and cleaning up the rest of the BFFs to also use the Playlists VAS to handle the many different playlists-related endpoints.

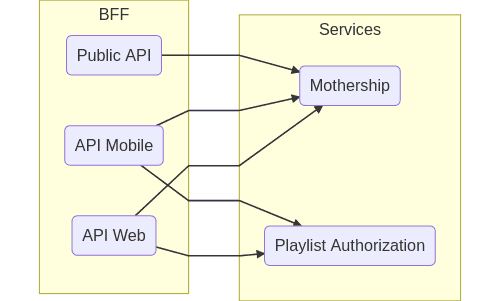

The following graph illustrates the process of migration:

As you can see, the main SoundCloud APIs were calling directly to the Mothership (the original SoundCloud app which is the main interface to our databases) and to Playlist Authorization (a system that authorizes users according to business rules of tracks in a playlist). This summarizes the two main problems of this approach: duplication of logic in the BFFs, and fragile authorization.

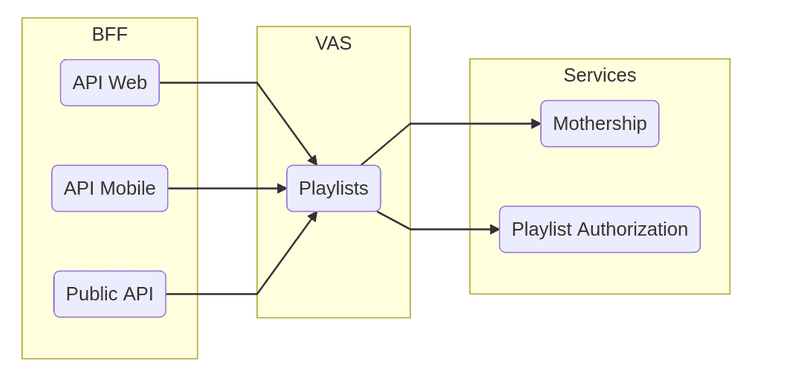

The following graph shows our solution:

With this architecture, all the logic is centralized in the Playlist VAS.

This project was divided into the following steps:

- Extracting the logic from the BFFs and creating a new Playlist VAS. We investigated and documented all the different implementations of playlists logic in our main services to come up with the base logic for playlist-fetching logic. Once we documented all the information needed and collected feedback from the rest of the organization, we implemented the service.

- Automatic tests to ensure that centralized logic matches refactored services. We added unit tests to ensure that we covered all the possible scenarios of fetching and authorization logic for playlists. We also added integration tests to ensure that response formats with clients weren’t broken, and that integrations with dependent services were working properly.

- Migrating the BFFs to use the Playlists VAS. This might seem like an easy step, but it actually took us longer than implementing the service itself. We had to migrate more than 50 playlist-related endpoints from the main BFFs. We did this endpoint by endpoint, and by carefully comparing responses from both implementations, as we didn’t want to break anything from the clients of the BFFs.

What We Learned

VAS comes with many benefits, and it was a logical solution for the problems seen with playlist resolution at SoundCloud. The first and perhaps most obvious mitigation was that a Playlists VAS reduces duplicated playlists code in the BFFs. Each BFF contained the same logic for orchestrating various calls to dependent services for resolving playlist metadata, but with a VAS, we could congregate this logic in one service. Having a centralized service containing business logic means refactoring and optimizations are easier and faster. This also helps simplify cross-platform feature development, as value objects — in this case, playlists — are only exposed in a central place. So it becomes trivial to the rest of the clients to access playlists instead of reimplementing that functionality in each BFF.

One of the most critical parts of fetching playlists was authorization: Leaking private or unreleased tracks to the general public is a worst-case scenario we want to avoid at all costs. Authorization logic was spread out over multiple services, increasing the risk of inconsistencies (and therefore vulnerabilities) sneaking in over time. The Playlists VAS means having one central codebase for authorization logic, which can be audited easily.

It’s worth noting here that VAS-to-VAS communication can occur in some circumstances. Let’s say, for example, that a request is sent over to the Playlists VAS to add a track to a given playlist. Before we continue with this write command, we must first check that the track is visible to the session user. Authorization logic for entities is centralized in the VAS, so we’d have to make a request to the Tracks service to determine whether the requested track is authorized to be added. In this case, we ensured that the previous logic for tracks that has depended on playlists was decoupled, meaning we can have VAS-to-VAS communication without circular dependencies.

Considerations

The migration of entities to their own services has as many benefits, as outlined above. However, implementing this solution has downsides as well, including:

- Adding a new service to our systems. Creating a new VAS comes with maintenance costs and infrastructure costs. We need to provision new nodes, deploy the monitoring service, maintain a new codebase, add a new service to our on-call rotation, etc.

- Network latencies. In previous implementations, when BFFs wanted to fetch playlist metadata, they just needed to do a round trip to Mothership and Playlist Authorization. With this new implementation in place, they need to do an extra roundtrip to the Playlists VAS.

In addition to considering downsides, we also considered the alternate solution of having the Playlists VAS as an external library that would be linked during the app build process. This is an approach we used in the past — for instance, with our JVMKit library (you can read more about that here). However, this solution comes with extra complexity and risk, in that different versions of the library could be used in each service, potentially causing a state with diamond dependencies. In our case, the benefits of introducing a VAS far outweigh the tradeoffs.

It’s also worth mentioning that the approach of using a VAS means we can expose new integrations using Twinagle, which is an in-house implementation of the Twirp protocol for Finagle. You can read more about the motivation and benefits behind Twinagle in our related blog post, but one bonus is the added ease of integration and maintainability. Twinagle uses an interface description language (IDL) to generate server stubs and clients, meaning that integrating services have a clearly defined API to work with. Making changes to the VAS therefore becomes safer, given that the API contract stays consistent and will clearly expose any (backward compatible) changes made, with all implementation details being encapsulated behind the API.

Summary

The adoption of Value-Added Services at SoundCloud has been well received. It allows for a cleaner architecture and a better separation of concerns. We’re definitely going to move more entities to their own VAS and extend existing ones to have more operations, all of which allows us to have a clear roadmap for the architecture of our microservices.

In the next blog post — and the last one in this series on the evolution of Service Architecture at SoundCloud — we’ll talk about the next iteration of Value-Added Services and how they evolved into Domain Gateways.