A Better Model of Data Ownership

Once upon a time, we had a single monolith of software, one mothership running everything. At SoundCloud, the proliferation of microservices came from moving functionality out of the mothership. There are plenty of benefits to splitting up features in this way. We want the same benefits for our data as well, by defining ownership of datasets and ensuring that the right teams own the right datasets.

In this post we’ll briefly recap the motivations for splitting up the monolith, describe what we mean by ownership of (micro)services, and see that the responsibilities of ownership apply to datasets too. With the help of some examples, we’ll see how to decide who should be the owner of a dataset, where the costs arise when ownership is in the wrong place, and the visibility concerns that are addressed with this stronger definition of ownership. Finally, a brief word on the task of getting from where we are to a closer adherence to this model.

Recap: why split up a monolith?

It’s much easier to keep cohesion high and coupling low when there’s a boundary between components. We know this from writing code, where we split code into smaller pieces when it gets too large.

At the level of building services, that split might be across modules or code repositories, and access might be over HTTP. Defining these interfaces between components allows you to design a clearer architecture, and often leads to simpler maintenance, though at the cost of complexity that comes from communicating over the network.

Clear interfaces also reduce the coordination required when multiple teams work together. The teams agree on the interface, what the data and schema looks like, and can then work independently to build and maintain components. This also allows the system to scale as teams grow independently.

We saw the lack of clear interfaces within our monolith create problems. It cost more time than it should have to make progress on features, and cost more to maintain them. Importantly, these costs of working with a feature were often not visible because they were distributed around everyone who touched it – which, in the monolith, meant everyone.

All of this has been covered before. The important point is that clear interfaces allow us to define ownership of the features exposed through these interfaces.

What is ownership?

Ownership of a service brings a number of responsibilities to a team. These include

- availability and timeliness – clients should be able to access data and operations provided by the service, and expect the data to be up to date (whatever that means for this service).

- quality and correctness – the service should do what was agreed with its users, and when it doesn’t the owner should fix the bugs. This puts a burden on the service provider to manage, for example, the lifecycle of response schemas in a way that its clients can handle.

- identification of consumers – the service owner should know who their users are, so that when changes are made they can be negotiated with the consumers before breaking things elsewhere.

The key insight is that none of this is specific to services. All of these responsibilities apply equally well to an owner of a dataset, a piece of shared infrastructure, or really anything that is an integration point between two teams! This is because a service is just one way to provide an interface to some data, giving a way to read and modify the backing dataset.

What does ownership mean for datasets?

Similarly to owning a service, owning a dataset means that you have the responsibility to produce data according to some contract with your consumers. Data should be available within some understood time window and should be correct according to that contract. As the producer, you have the responsibility to fix problems with the data.

You should also be able to know who your consumers are. This visibility makes it possible to make changes to what you publish over time. There are technological fixes for this. With services this can be done by authentication/authorisation on the service, something simple like requiring a request header stating who the client is, or more sophisticated such as distributed tracing. With datasets you can monitor access to wherever the dataset is stored (e.g. reads from HDFS or an RDBMS), or adopt more asynchronous ideas like scraping for dataset locations and the jobs that read/write them, and building a dependency graph between them.

How do you decide who’s the owner?

To begin with, the owner of a dataset must also be the producer – the team that runs the process that creates the data. This is because the owner can only fulfil their responsibilities if they have control over writing the data.

There are two main factors that come into deciding which team should be the owner. We’ll go through them both here with an example. These two ideas are enough to reason about the ownership of a lot of datasets. (There are also cases where it may be clear that ownership is currently in the wrong place, but where there isn’t a clear team that should own it. This includes datasets that are populated from multiple sources, where ownership of an entity is shared between teams.)

Semantics

The team producing a dataset should be the team responsible for the semantics of that dataset. Equivalently, a team not responsible for the semantics should not be producing the dataset.

A dataset is only meaningful with some definition of the information in the dataset. Many teams might have some idea of what a dataset means, but only one team has the responsibility of designing and evolving the semantics. That team should be the owner of the dataset.

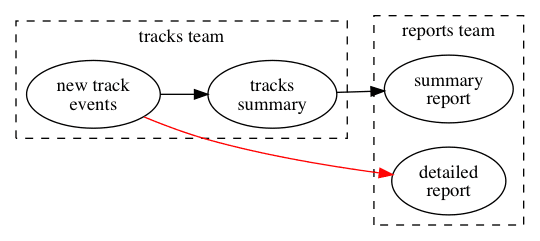

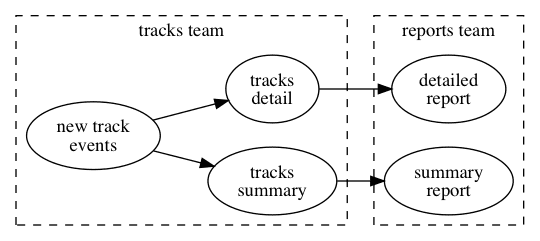

We see teams trying to rebuild views of datasets from elsewhere in order to fit their precise needs. In this toy example, suppose that this Tracks team creates an event (in the event sourcing sense) each time a new track becomes available on the platform, and uses that to build a dataset summarising all of the tracks. Parts of that process might be simple (e.g. showing counts of tracks, totals of media length), but some may be much more complicated (e.g. tracks have geographical permissions modelled in a different system, and we want to summarise the number of tracks per country).

Now consider a Reports team using this information to build reports. If they need more than a summary, the published dataset may not be enough. A direct way to get the information they need would be to read all of the events that went into that summary, and build the new dataset themselves. But that requires knowledge of all of the details of tracks and the permissions model and for all of that to be exposed in the events. The logic will be duplicated in the two teams, separated from where it should be. This leads to a high risk of inconsistency in different views of data.

At the start of a project using this data, it would be difficult to predict the cost of the work, because the expertise is in the other team. Over time the cost of maintenance of the dataset is also hidden (and larger) because the work is distributed around the consumers. When the semantics of the data change later, it will be easy to miss making the required change everywhere. Handling this all in events can be particularly difficult, because changes to the schema require manipulating the history of events.

A better solution is for the work to be done in the team that has full knowledge of the semantics and the responsibility of maintaining the dataset. In this case, the Tracks team should build that dataset with enough information for the consumer, and the Reports team should use the published dataset. It’s clearer what the costs are and work is not duplicated. When changes happen to the semantics, the owning team simply publishes a new dataset.

Encapsulation

Don’t consume data from other systems’ internal data stores

The internal data structures of a component (of any size: system, service or single class) are non-public so that invariants can be maintained. Other parties (calling code, other teams) get access through an interface. This level of indirection through a published interface allows the owner of a system to make changes to the data store without other users having to coordinate.

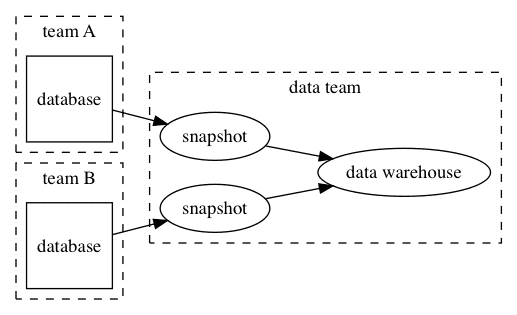

In this example, consider how data gets from various systems in the company to a data warehouse used by data analysts. Such a tool can be great for analysis (find all of the data in one place, easy to query) but can lead to problems of maintenance later.

Consider a tool to take a full snapshot from a database and push it to the data warehouse, where it’s available with the same schema and data as at the source. This provides a really easy way to get your data into one place. But it also couples the data warehouse to the internal database of your service – specifically it couples together the schema of your database, the data warehouse, and any query that reads that data and expects a certain schema. When you want to change your supposedly-internal database schema, you suddenly have to coordinate with a lot of downstream users. Worse, given that the data warehouse is a centrally accessible resource, you probably can’t know who those users are.

This setup has made the internal database an interface to the data, breaking the system’s encapsulation.

Indirection to the rescue. Rather than using the snapshot tool to copy from the database to the data warehouse, you as the team producing the data should copy the data somewhere else, say on a shared filesystem such as HDFS. You’ll need to define a schema for the snapshot, even if this is (initially) only a representation of the source schema. You’ll want to consider the design of this interface, too. For example, include only the fields you need first, adding others later as required. As the schema evolves you’ll need to think about backwards compatibility, to ensure that consumers will continue to be able to read the data.

This approach gives a new integration point, and a way to decouple the lifecycle of your database schema from that of your consumers. This doesn’t solve all of your problems (what if my schema has to change in a way that isn’t backwards-compatible?) but it does give a place to start and makes it easier to manage those more difficult changes.

What does this mean for my team?

Overall, the point of arranging ownership better is that as a company we spend less on maintenance. This will mean work moving between teams and consolidating in a single place per dataset. In some cases this will mean a team needs to take on more work; in some cases less.

Let’s look at the viewpoints for a few different roles.

I’m a producer

Where you produce data there is an expectation that it should be exposed appropriately to consumers who need it. This may mean some new work to understand their requirements and build the integration. You should understand the severity of failure or data loss on your consumers.

Where there are existing dependencies on data you own, but where you don’t own the process that produces that dataset, there is an opportunity to remediate technical debt. This can happen by introducing a publishing workflow that you own and that makes sense in your domain, and negotiating usage with consumers. Your consumers will then have much easier access to this data, and you will be in control of all of the moving parts when you need to make changes.

I’m a consumer

Where you consume data, there is an expectation that you do less rebuilding of datasets, and instead, negotiate with the producer of your data to have them produce it in an appropriate form.

Where you are already building datasets whose semantics you don’t control, work with the team that should own the dataset so that they produce and publish the data you need in a way that’s appropriate for both. This may be as simple as the producing team running an existing job, or may involve asking them to build something new to expose the data.

I’m a product owner

Where you own a feature, consumers of the data generated by your feature are your users too. When considering priorities for your team, you’ll need to balance the needs of your internal data consumers with those of your external users.

Show me the data!

How can this work in practice? A common fear arises when you need some data, when it isn’t available in the right form and when your project is short on time. It may appear quicker to build the data yourself than to request that the work be prioritised in another team, where you’re competing for attention among their other priorities.

There are essentially three options that distribute the initial cost (writing the job to produce the data) and the ongoing maintenance cost. Either way, the code to produce the dataset has to be built somewhere.

- consumer builds and owns – the consumer takes on all of the cost and the wider organisation takes no shared benefit

- consumer builds, producer owns – the consumer, in cooperation with the producer, builds the dataset and then hands off ownership to the producer. The consumer takes the up-front cost, the producer takes the longer term cost, and the total future cost is reduced because no-one needs to duplicate the implementation.

- producer builds and owns – the producer does the initial work and takes all of the cost, and again the benefit is shared. This is the no-compromise approach, and may not be possible in short-term due to balancing other priorities.

In any case, the outcome of this project should be that a curated dataset exists, the dataset is owned by the producer of the data, and consumers integrate with this and not the source data.

Conclusion

When accessing and using data that is owned by other teams, certain patterns lead to high costs of maintenance that are not apparent at the start. It can be difficult to track these costs later when they become distributed around multiple teams.

As a consumer of data, avoid building datasets whose semantics you don’t own, because it’s duplicate effort and you leave yourself at the mercy of future changes you don’t control. Use published interfaces to access data; asking the producer of the data to create one is preferable to doing it yourself or accessing their internal data stores directly. As a producer, it’s important to think about how the data your feature generates will be used, and how to expose to other teams in a way that doesn’t spread maintenance responsibilities.

Following these two principles should make it easier to keep your data integrations well understood and maintainable, by giving better visibility over data that is shared between teams.