Radical Candor: An Experience Report

Although it can be easy to know if you’ve messed up badly as a manager, it’s not always as easy to know if you’re doing a good job. In particular, the power dynamics at play can make it hard for people on your team to feel confident letting you know what’s working well and what’s working not so well.

I’ve been managing managers for a while now, and through the years, I’ve tried a few ways to help close this gap. In this article, I’m going to talk about an approach I started using in the last few years that seems to strike the best balance of getting the input managers need while still promoting a healthy culture of direct feedback.

The Approach

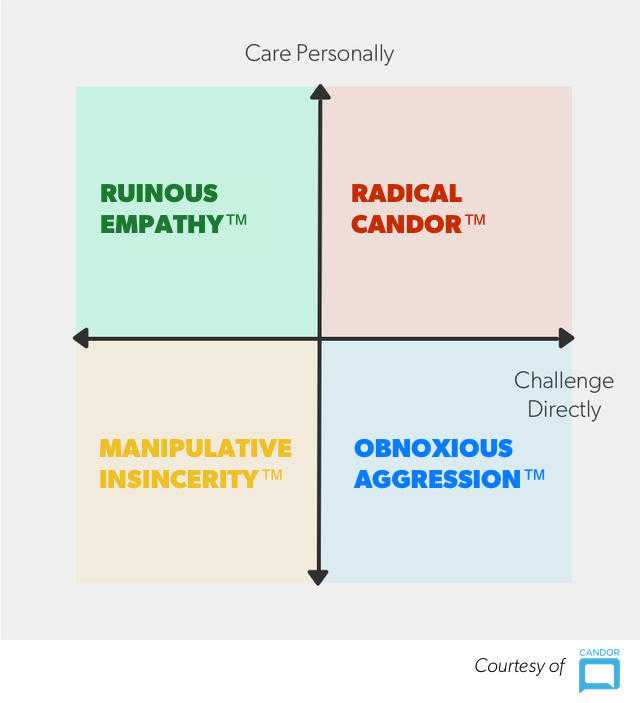

Back when I was working at Sky, I came across a post by Kim Scott entitled “Radical Candor — The Surprising Secret to Being a Good Boss.” The title was intriguing enough to get me reading, but what I discovered was an approach to management that was genuinely refreshing. The following diagram is a great summary of the core concept and some of the terms she uses:

I loved the concept, especially since it challenged some of my own tendencies toward “Ruinous Empathy” — caring personally for my coworkers but failing to challenge them directly — and gave me a path to provide more meaningful support for my team.

The book that followed (see radicalcandor.com) is a treasure trove of tools on how to put these ideas into practice, and it contains a section dedicated to the Manager Guidance concept introduced in Kim’s original post.

One aspect of this concept is a skip-level meeting, which is generally defined as a meeting held between a manager’s manager and their direct reports, thereby skipping the level between them. Generally speaking, Kim’s Manager Guidance process follows these steps:

- A skip-level meeting is held specifically to ask people how their boss could become a better manager. During this meeting, notes are collected and then shared with the manager after the session.

- A follow-up discussion takes place between the manager and their manager to provide additional context about the feedback and answer any questions.

- The manager then speaks to their team about what they learned from the feedback and what changes they intend to take in addressing it.

The specific topics people raise in the skip-level meeting are interesting and useful, but most importantly, we want to learn whether people feel good about the feedback culture between themselves and their manager.

My first attempts in using the process at Sky revealed a lot, but for this article, I’m going to focus on how it worked here at SoundCloud, as I was able to put into practice some of what I learned from the first time around. I’ll explain more about how I prepared for the sessions, how I ran them, and how they were received by the teams and their managers. I’ll also cover some of the ways in which they could go wrong and how to address these potential issues.

Preparation

First off, any manager having this process run on their behalf needs to be bought in. They should at least read Kim’s blog post, but better yet, they should read the relevant chapter in Radical Candor, and ideally, the entire book! If, after all of that, they aren’t excited, then it’s better to find a different approach for their guidance.

When teams are invited to a manager guidance session, I provide them with key information. An example invite might read:

This session is to gather feedback to help [your manager] be a better manager. It’s based on a framework Kim Scott talks about in her book Radical Candor, and when I used it (both for me and by me) in a previous company, I found it to be a really helpful exercise.

I recommend reading the entire article here, but the TL;DR about this session can be found in the section starting “Make it easier to speak truth to power.”

There’s no need for you to prepare anything; I’ll capture notes and ask questions to help keep the conversation on track. [xxx] and I want you to feel confident about being completely open.

Running the Session

Structure and Process

In the Radical Candor book, Kim recommends a very specific structure for the meetings, which I mostly followed, as it works well. Here’s how I interpreted it for my use:

- Short introduction (c. 5 minutes)

- Open discussion (c. 40 minutes)

- Reviewing notes together (c. 15 minutes)

As the moderator, I capture notes and I display them on a screen behind me so people can see my terrible note-taking skills in real time and tell me when I capture their points inaccurately.

Introduction

On rereading Kim’s book recently, I realized I had forgotten to apply one piece of advice, which was to get the managers to explain the purpose of the meeting to their teams ahead of time. This meant that a very small percentage of people attending the meeting knew what to expect.

I was anticipating this, so I included time at the top of the session to run through the purpose and set some ground rules. Some of the key points I called out are:

- This is about helping the manager learn and grow.

- The session shouldn’t focus exclusively on either positive or negative points, as it’s all about getting balanced feedback.

- It’s also about checking in on the flow of feedback between the team and their manager.

- Everyone’s voice needs to be heard.

- The notes are not attributed to individuals, but people still have to be comfortable with them being shared directly.

Topics

I wanted to have some consistency in approach across the sessions (I have five managers reporting to me), so I came up with a loose structure as follows: For Me, For My Team, For the Company. In each section, I explained the overall topic and then used simple starter questions to get the conversation going.

I tend to go with somewhat neutral and uncontroversial questions so as not to push the conversation in a particular direction, but rather see where it gets taken by the group, and I then dig deeper when something interesting emerges. However, sometimes if I know there’s been a particular theme that’s affected a team (e.g. confusing priorities or a visible conflict), I might ask specific questions about how their manager handled it.

The questions you ask can reveal a lot about what you expect from managers on your team, and that’s not a bad thing! At SoundCloud, we recently completed an exercise to define expectations for Engineering Managers, and I expect I’ll start using some of these expectations as a basis for sessions in the future.

For Me

This section gives the attendees the opportunity to talk about how their manager supports their specific needs as an individual. Some example starter questions I used:

- How often do you get together 1 on 1? Is that the right cadence for you?

- Who controls the agenda for those sessions? Do you get to talk about everything you want to? Do you ever talk about your career plans/aspirations?

- How available is your manager to you outside of those sessions?

- Does your manager actively seek out opportunities for you that align with your aspirations?

- Does your manager ask you for feedback? When did you last give them critical feedback? How did they take it?

- Do you feel that you’re learning from your manager? Do you have any specifics?

For My Team

This section is all about the health of the team as a unit and the manager’s contribution to that. Some example questions are:

- Do your team meetings run smoothly? E.g. clear purpose, kept on track, actions logged, everyone is heard.

- Is collaboration encouraged? Does your manager seek to avoid silo-ing of knowledge/skills?

- Do you have social events as a team that everyone can engage with?

- Do conflicts within the team get resolved?

For the Company

This section is about how the manager contributes to the success of the relationship between their team and the rest of the business. Here is an example of some of the questions:

- Is it clear the role your team plays in the company’s success? Do you think you’re working on things that contribute to that?

- Do you feel that the successes of your team are known about in the rest of the company? Are you well represented in key meetings, e.g. All Hands?

- Does your manager advocate for you as a team when you raise topics that need assistance from outside of the team?

- Do you get clear information about changes to company priorities or policies from your manager? Do they manage to answer all your questions, or at least point you in the right direction?

After the Session

Once the session is complete, I plan a note review session with each manager, and I share the notes with them the evening before. This gives them enough time to digest the information and have questions prepared, but not so long that they stew on any negative points.

The session itself is around 30 minutes long, and I set expectations around the next steps, which start with the manager summarizing the key learnings from the notes and what changes they plan to make. They should then talk through these ideas with their team to reinforce the message that the feedback is being heard and acted upon.

How Did It Go?

How Was It for the Teams?

Probably the most common piece of feedback I received was along the lines of: “That wasn’t as bad as I was expecting!” It can be stressful to think about giving feedback to your manager, so a process that normalizes and encourages it can bring relief to many people.

Here is an explicit piece of written feedback I received:

“…I found that session really really nice. I was very apprehensive going into it, but in the end I think it was one of the most comfortable feedback-collecting formats I’ve been a part of. It was so nice to be able to talk and have someone else write it down, to be able to hear what other people had to say and triangulate, and to frame the whole thing as guidance and direction rather than feedback…”

The other realization I often see dawning on people during the sessions is how difficult it is for a manager to tailor their approach to a group of diverse individuals.

What Feedback Was Given? How Did the Managers React?

Thankfully, there were no major surprises in the feedback for any of the managers in my team, but there were plenty of items they were able to take forward and work with. I had universally positive responses from them, and when we talked about the approach with other managers outside of my group, it was great to hear them advocating for the process and the value it brought them.

For some managers, people on their teams were asking for more critical feedback on their work, as they wanted to understand more deeply how they could grow. Other managers who had focused attention on that already heard that they should also apply the same rigor to giving positive feedback, which is a theme in Kim’s book too.

What Did I Learn?

One piece of advice I didn’t follow from Kim’s book, as mentioned above, is to get the managers to explain the process to their team in advance, which would definitely have saved some time in the sessions. Some people weren’t sure whether their manager would be there and even whether they would be on their own in the session.

The other thing that is clear is the time in the feedback sessions passes very quickly, so it’s important to be very structured about moving through the topics and try to avoid getting stuck on any particular point for too long.

What Could Go Wrong and How to Address It

Gripe Session

If one or more people in the group choose to use the session to moan about their boss, it can be quite detrimental to team morale. Also, as Kim points out in her book, there’s a danger that the moderator can appear to presume that the boss is guilty, or — just as bad — try to defend them against the criticism. Having said that, the complaints are a window into a problem within the team that benefits from being revealed.

The moderator can steer the conversation to avoid getting stuck on a topic that might only have relevance for a small subset of the group, e.g. “[xxx], does this affect you as much as it affects [yyy]?”

No One Talks

One of the reasons I like to be prepared with a set of questions is that sometimes it can be hard to get the feedback flowing with certain teams. I tend to think that’s not a great sign about the feedback culture, but it can also just mean people are reserved and need help exploring the topic. This is also why I like to start with neutral/factual questions that everyone can feel good about answering, like “How often do you have 1:1s?”

Only a Subset of People Talk

Often, teams contain natural leaders aside from their manager, which can lead to interesting dynamics wherein those people can try to steer the conversation on the moderator’s behalf. Reminding the group that the guidance needs to be based on feedback from the whole team can help keep these people from dominating the conversation.

The Group Is Too Big/Too Small

So far at SoundCloud, I’ve run this process for five managers, and the groups attending the sessions have varied in size from three people to seven people. That’s probably a good range, as with only two people, it’s very obvious when collecting the feedback that it’s going to be directly attributable. I would consider 1:1 interviews in such a case.

With a larger group, it’s more difficult to manage the collection of the feedback and make sure every voice is heard. Running multiple sessions to cover the full group is a good alternative in this case. This can happen naturally if the team structure already implies a way to split the group — for example, backend and frontend engineers.

The Process Blocks Direct Feedback

One risk that a previous team member of mine called out is the possibility that people lean on this process as a way to avoid giving direct feedback to their manager. This is valid, and it’s one of the reasons why Kim recommends not running the process too frequently. In the Radical Candor book, she suggests once a year, but I personally think twice a year will be fine for us, since we have rather dynamic teams and the managers on my team are keen to have more frequent check-ins.

I haven’t personally run a follow-up session with a team before, but a key part will be to discuss how successful the manager’s attempts to address the previous feedback have been. Additionally, I would want to find out if there is any change in how confident people feel about giving direct feedback to their manager.

Some People Can’t Make It

It can be difficult to schedule the sessions so everyone can make it along, and there are always going to be situations, like sick days, that mean the whole team can’t get together at the same time. When this has happened for sessions that I’ve run, I have shared the notes with the people who couldn’t make it and asked them if they had anything to add. If they did, I asked them if they either wanted to provide those as written notes, or if we should meet face to face to discuss. I also make sure this is all completed ahead of the review session with the manager.

Bad Notes

The notes are a key output of the process, so the time taken during the session to review them is critical. Whenever I’ve run these sessions, we’ve found ambiguities or confusing language that we’ve been able to correct as a group. It really makes a big difference to how much the manager can get from the process if they can refer back to these notes and get a clear reminder of what they need to address.

Conclusion

A few years ago, Google published some amazing research on the key dynamics that set successful teams apart from other teams at Google. By far, the most important element of this was Psychological Safety, which they defined as: “Team members feel safe to take risks and be vulnerable in front of each other.”

A healthy feedback culture is fundamental to establishing this Psychological Safety, and my experience with using Kim Scott’s Manager Guidance approach is that it can really make a positive difference in that culture. If you’re a manager, why not ask your manager to run this process for you? I’m really looking forward to hearing the feedback that comes from mine!